On Wednesday I’ll be chairing Innovative Learning: Maximising Technology, Maximising Potential. I have written a piece on taking a more critical approach to deploying technology here, and this complements the short presentation that I will make, and which is on my slideshare.

I will make the following points, which connect to two recent journal articles.

- Towards a resilient strategy for technology-enhanced learning.

- Questioning Technology in the Development of a Resilient Higher Education.

FIRSTLY. At DMU we are engaging with the following questions.

- What is the place of technology in the idea of the University?

- How do technologies help us to realise or diminish our values, and how do they impact the social relations that emerge around these values?

- Can strategy for embedding technology relate it to the broader humane activities of the University?

In addressing these questions we are developing an approach to the use of technologies in the curriculum that supports:

The transformation of learning by staff and students through the situated use of technology.

Our approach has amplified issues around the following [risks].

- How do we manage issues around curriculum control and change-management? How do we balance ad hoc curriculum design/delivery in programme teams with a perceived need for strategic/institutional control? In this approach, how do we enable staff digital/technical literacies?

- What technology-related support and skills do we retain and nurture in-house? Do we just retain those that enable us to develop our quality/distinctiveness, or just those that are interesting?

- How do we manage elasticity of demand and new service-provision? How do we develop technologies that will enable emerging and future web applications? [See Scott Wilson’s recent presentation on this issue]

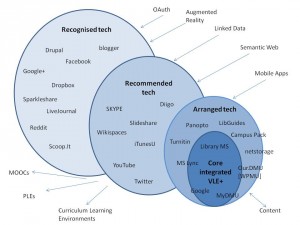

SECONDLY. We are trying to address or refine a model for the institutional implementation of technology that maps across to work started a Manchester Metropolitan University, under Mark Stubbs. They worked-up a Core/Arranged/Recommended/Recognised model for the use of technology stemming from their VLE Review in 2009.

Core: integrated corporate systems, including VLE, portal, library, streaming media and email, are available to students/staff to use with the devices and services of their choosing, and extended through tools that the institution arranges, recommends or recognises.

Arranged: accounts are created on key plug-ins or extensions beyond the core, like plagiarism detection tools, user-generated content tools and synchronous classrooms.

Recommended: recommendations are made with supporting training materials, for connecting key, web-based tools seamlessly into the core/arranged mix. This might include using RSS to bring in content from Twitter, SlideShare, iTunes or YouTube, or supporting SKYPE.

Recognised: the institution is aware that students and staff are experimenting with other technologies and maintains a horizon-scanning brief, until and unless a critical mass of users require integration.

A representation of this at DMU is shown below.

However, in moving this forward we are now thinking about how we do our work in public, rather than in an enclosed set of spaces. The work of the CUNY academic commons and of the ds106 community has been important for us here, in demonstrating that spaces might be cultivated and opened up in different ways by different communities at different times, and where the rules of engagement are determined through negotiation. This means that governance is also important and is actually negotiated with the academic community, rather than done to them.

THIRDLY. Governance and enclosure. We are having to think closely about what might be termed our corporate and personal assets, but which we might also refer to as personal or corporate data, or research/teaching/learning outputs or resources. A key issue surrounds out-sourcing or hosting, as opposed to in-house developments. Our IT Governance Team are helping us to think about the implications of the Patriot Act in the USA, and how our use of the cloud might be affected.

In particular, we are addressing issues of pedagogy and how they relate to: service resilience; confidentiality/privacy; copyright/copyleft/content distribution; data security/back-ups; control/deletion. Im portant here is the realisation that

The cloud has its own challenges, not least of which is the fact that the name can lead non-tech savvy folks to imagine that their data is bits of magic floating about in the ether rather than sitting on a server subject to the laws of the land in which it is located. There are concerns about ensuring safety of information. Additionally, there are potentially big problems with ‘offshoring’ corporate assets outside of corporate governance.

So we are thinking about risk-management at a range of scales: does it matter if someone accesses your stuff? [c.f. Dropbox; personal emails subject to FoI, as seen in Leveson].

We are also thinking about corporate governance, including access to services that are marketised? [Google-Verizon and a two-speed internet; costs of accessing data in marketised HE?]

We are also wondering about what happens if the personal circumstances of the academic who is responsible for a specific course or programme change and we cannot get access to core student information, like assessments? [What should be managed in-house or hosted via a contract?]

We are asking whether users and the institution understand that data is being transferred into a service and that we/they have responsibilities? [T&Cs; IP; protected characteristics; indemnities for libel.]

Finally, we are beginning to ask how do we work-up the digital literacies of our staff/students in this space? [We have some emergent staff guidelines and some guidelines for our Commons.]

FOURTHLY. This takes place against the backdrop of a world that faces a crisis. We might view this as a triple crunch of economic crises of scarcity/abundance and finance capital, of liquid fuel availability [including peak oil], and climate change.

- There is a strong correlation between energy use and GDP.

- Global energy demand is on the rise yet oil supply is forecast to decline in the next few years.

- There is no precedent for oil discoveries to make up for the shortfall, nor is there a precedent for efficiencies to relieve demand on this scale.

- Energy supply looks likely to constrain growth.

- Global emissions currently exceed the IPCC ‘marker’ scenario range. The Climate Change Act 2008 has made the -80%/2050 target law, yet this requires a national mobilisation akin to war-time.

- Probably impossible but could radically change the direction of HE in terms of skills required and spending available.

- We need to talk about this because education and technology are folded inside this narrative, and because education and technology are tied into narratives of economic growth.

We might then begin to discuss futures and the role of innovative learning in a disrupted world. Facer and Sandford wrote about four principles that underpin futures thinking.

Principle 1: educational futures work should aim to challenge assumptions rather than present definitive predictions.

Principle 2: the future is not determined by its technologies.

Principle 3: thinking about the future always involves values and politics.

Principle 4: education has a range of responsibilities that need to be reflected in any inquiry into or visions of its future.

We are trying to engage with these on our DMU Commons, which serves as an idea of what the University might become in public. This includes thinking about how to situate technologies within critical pedagogy and the communal activities of the institution. This is important because institutional planning needs to focus upon the provision of secure core institutional spaces that enable staff and students to position and become themselves, and to act in the world. Strategies like a programme-of-work that aligns key events, data, processes and technologies may help to develop a blueprint. Such a blueprint needs to reflect institutional values, and legitimise the activities of ‘mavericks’, or those on the boundaries or edges of engagement with institutional services.

Pingback: Heads of e-Learning Forum meeting report – 13th June 2012 – University of Kent | eLearning@Liverpool