NB. this is not a blog-post. It is an essay. It is too long, so probably best not reading it. Do something else, less boring instead.

There is a PDF version here.

ONE. The political economy of transition and separation

We know that higher education institutions are relying upon staff to own the risk of transitioning their working lives online and to refocus upon remote working. We know that this transition is overlain on top of extreme uncertainty about families and friends, potentially alongside fears or anxieties about their own well-being. This transition is structured around separation from loved ones, from peers and collaborators, from students, and from union representatives. This separation and estrangement, as our self-managed reaction to the virus that has infected our society, has revealed the weaknesses of our existence inside our political economy.

This political economy wants us individuated, atomised, separated out, and estranged from each other, in order to prevent collective organising and the sharing of experiences. Through such isolation, the managers of Capital can constantly reframe the relations of production that bind us to the machine, and use new forces or technologies of production, or new organising principles for productive activity, to discipline our work and drive efficiencies or overwork. For Capital this is a question of life and death, because without access to and control over our living labour, it is nothing. Yet it demands that we are made more efficient, or that we bring more infrastructure or resources into productive activity, and that we empty-out our time of our existing activities through acceleration or speed-up. In this way, we are called to expand our available time into new recruitment markets, accelerated programmes, public engagement or impact activities, or the need to subsume our lives under work because workload allocations are bullshit and how else will we do research?

Thus, we face the intensification of work, or our redundancy from it, because of Capital’s contradictory bipolarity that demands that it annihilate labour time on the one-hand, whilst at the same time it measures its wealth in relation to that labour time. The exhaustion of this constant movement of contradiction is borne by those condemned to labour.

Capital itself is the moving contradiction, [in] that it presses to reduce labour time to a minimum, while it posits labour time, on the other side, as sole measure and source of wealth. Hence it diminishes labour time in the necessary form so as to increase it in the superfluous form; hence posits the superfluous in growing measure as a condition – question of life or death – for the necessary. On the one side, then, it calls to life all the powers of science and of nature, as of social combination and of social intercourse, in order to make the creation of wealth independent (relatively) of the labour time employed on it. On the other side, it wants to use labour time as the measuring rod for the giant social forces thereby created, and to confine them within the limits required to maintain the already created value as value.

Marx, K. (1857/1993). Grundrisse: foundations of the critique of political economy.

Institutions act as containers or nodes for the development of the general intellect, or those co-operative powers of science and nature, which are taken from individual academics through commercialisation or intellectual property or publishing agreements. They do so in association with educational technology firms, venture capital, private equity, corporate partners who have commissioned spoke programs, credit ratings agencies, publishers and philanthro-capitalists. They do so whilst regulated by governmental bodies focused upon competition and value-for-money, and this reproduces an HE system in which individuals, disciplines and institutions are individuated, atomised, separated out, and estranged from each other. The lack of symbiosis and mutualism places additional stress upon a system threatened by the interrelationship between medical and financial pandemics.

This led Bryan Alexander to write about COVID-19 versus higher ed: the downhill slide becomes an avalanche. Arguing that the pandemic accelerates privatisation, financialisation and cuts to public funding for education as a key service, Alexander writes of potential crises for institutional funding in relation to: the reprioritisation of limited local and national funding for community projects, social care, welfare and healthcare, rather than education; the potential for defunding allegedly unproductive strands of the HE sector (and in the UK pre-Covid-19, we know that there have already been restructuring proposals focused upon career-focused degrees, a Treasury focus upon productivity and human capital, and the use of longitudinal educational outcomes data to question the value of the Arts); a risk to endowments and advancement projects; new forms of philanthro-capitalism, which aim at forms of structural adjustment; the rejection of higher education as an investment opportunity for families, leading to a decline in enrolment, including from international students; and the need to refund existing students.

The pandemic exacerbates the ongoing secular crisis of capitalism, through which: stable forms of accumulation cannot be found; austerity is normalised at the level of society; there is a lack of profitability and productive investment, and a concomitant obsession with productivity; a focus upon economic populism in the face of declining output; quantitative easing replenishes the balance sheets of banks and finance capital rather than of citizens to enable compensatory consumption; and on and on. This infects the University as it is subsumed under the law of value, which demands that its activities are recalibrated through performance management, commodification, marketisation and competition written into law and underpinned by regulation. Thus, inside our institutions there is a constant clamour for surplus labour, time, value and wealth materialised as money in this persistent secular crisis of the University.

TWO. Frozen surplus populations

Capital’s question of life and death bleeds into the corporeality of the institution, in which there is a constant clamour for the proletarianisation of labour-power, through an attrition on labour rights, work intensification, unbundling and deskilling, and the generation of surplus populations. This latter issue is picked-up by Colleen Flaherty in discussing frozen searches in the USA in response to coronavirus. She notes that this includes delayed start times for some new roles, and she quotes the University of Minnesota, HR department:

to allow time to plan a productive onboarding and orientation processes, and to make needed adjustments to responsibilities to ensure new employee productivity and likelihood for success.

For Flaherty, these are signals of the risk of systemic collapse. However, we might question whether instead we will witness the collapse of unproductive capitals or businesses, in the shape of weaker universities. Those universities will lack the financial, intellectual or social capital, because they are overleveraged against particular income streams or levels of debt. Ensuring productivity and centring valuable, or commodity-based, human capital is the key, as adjustments are made by institutions, including freezing or furloughing, to mitigate against the risk of institutional collapse.

The mechanics of this are important because HE is riven by interlocking dynamics that reinforce separation and estrangement, and through which the medical crisis of the pandemic infects both the social by enforcing distancing, and the political economic by enabling a recalibration of the market for students, competition between individual academics, subjects and institutions, and the broader market for valuable and productive human capital. These interlocking dynamics feed off the quantification of academic value through the time spent on curriculum delivery or assessment, or the production of knowledge transfer and exchange, or the commercialisation of research, or the excellence of teaching or research. The quantification of academic value enables further separation between individuals, disciplines and institutions, such that the health of the sector is secondary to the health of individual institutions (NB this mirrors the political economy of association football, which is separated from its historical communities and overleveraged against debt and specific broadcast media revenue streams).

As a result, the sector is increasingly unwilling to support the staff who are a cost to it, rather than the students who are a source of revenue for it and the infrastructure around which it bases its activity. It increasingly demands unreasonable amounts of time from people who are scared, ill, overwork, precarious, caring, committed and professional, because it can impose discourses of efficiency, entrepreneurship excellence, impact and satisfaction, conditioned by the threat of precarity. Moreover, it does so in the knowledge that there is a vast, surplus population of available labour in the form of postgraduates who teach, graduate teaching assistants, unemployed PhD graduates, existing casualised staff, upon whom it can draw.

This threatens further casualisation of the academic labouring population, and enables it to extract surpluses by driving down its costs and weakening its labour rights. In response to these dynamics, Karen Kelsky has generated a crowdsourced list of institutions freezing the hiring of staff, including tenure-track jobs where ‘verbal offers that had progressed to negotiation have been revoked.’ In relatively uncertain times, or where working practices have to be re-engineered, it is easier to rely upon casualised or precarious labour that can compete for potential tenure opportunities at a later date.

THREE. Against leadership around casualisation

I wrote about this, arguing they all must go. But you will need another pot of tea for that one.

Of course, the Covid-19 pandemic has a differential impact, in terms of security for the most precarious, and the impact on labour rights through increased workload, bureaucracy and technological discipline. On 2 March, just prior to the UK coronavirus lockdown (such as it is) in the UK, an Open Letter to Students from Casualised Academics at UAL was published, with a particular focus upon the UCU strike #fourfights against: pay devaluation; pay inequality, based on gender and race; excessive workloads; and casualisation. The open letter points out how at the University of the Arts London, there is a population of 2,500 hourly-paid Associate Lecturers and Visiting Practitioners, responsible for the majority of frontline teaching.

The letter argues that for some this means precarious, fixed-term work with no prospect for promotion, tenure or funding for research, limited professional development opportunities, and the risk of receiving reduced hours over time. This also includes a lack of autonomy over workload, and a separation from departmental decision-making and peers. Such uncertainty and anxiety are amplified by the amount of unpaid work that is required to fulfil work commitments, alongside struggles to pay rent and bills, and put food on the table, let alone focus upon pension payments or savings. The knock-on is an explosion of ill-being for second-class academic citizens, who tend not to be white and male.

As the UAL casualised academics note: ‘the casualised, underpaid and insecure workforce who keep the university going on a day-to-day basis.’ Of course, this is not simply restricted to academic colleagues. We also witness ongoing protests about outsourcing of estates, cleaning and security staff in a range of institutions, alongside a range of struggles for pension rights, holiday and sick pay, and maternity/paternity rights. The composition of struggle and protest across the sector demonstrates how HE relies upon separated, estranged, proletarianised labour across academic and professional services staff. Moreover, the treatment of students-as-consumers or purchasers, and their weaponisation by management against academics, reinforces the separation and fragmentation of those who labour inside the University. Thus, far from the pandemic catalysing crisis, it simply illuminates the ongoing secular crisis of the University, and reveals the inner political economy of the institutional and sector-wide assault on labour-power.

Here, we are drawn to the leaked UK Russell Group minutes of March 2020 about the need to show leadership around casualisation, in particular to stop critics (democratically-mandated trade unions) shaping the agenda. These minutes include (3.2) the following drivers of casualisation: economies of scale in the curriculum; the split between teaching and research; research funding; and uncertain financial planning. It is noticeable that the minutes highlight the failure of teaching practices to evolve as a cause of increased pressure on staff, which then causes a run towards to fixed-term, teaching-only roles. This can be read as victim-blaming, with the argument not around over-recruitment or work-intensification, rather around ineffective or inefficient assessment regimes. Research Council demands around funding are blamed for proliferation of fixed-term research contracts. In terms of financial planning, the minutes move beyond coronavirus and Brexit to the flawed assertions around USS pension contributions and UCU disputes.

Here, institutions are simply dealing with the manifestations of inefficient processes imposed from outside or erupting from within. This leads towards the view from this privileged fraction of the sector that (5.1) the group must ‘ensure that our working practices and employment models are fit for purpose, recognising the diverse needs of staff, students and institutions themselves.’ Of course, those diverse needs are not equal and do not carry equal weight, and in this context, working practices and employment models have to be fit for the purpose of value-for-money, as stipulated by the Office for Students. Whilst the appendix to the minutes highlights how in 2017/18 the group had 11,435 zero hours contracts and 8,620 hourly paid staff, there was also an increase since 2012/13 in fixed term, part-time contracts. These numbers represent a lot of lives spent struggling for security. Elsewhere, it has been argued that institutions through UCEA have attempted to exclude fixed-term staff in turnover figures, in order to show the stability of the sector.

As noted by casualised academics at UAL, it appears that the sector relies upon a disposable workforce that its bosses wish to hide, and this includes those on student experience or short-term graduate roles. This brutal precarity has been signalled over and over as a symptom of the secular crisis as it infects the University, and that has been accelerated in the current Covid-19 pandemic. This has led to a campaign around #CoronaContract, with casualised staff demanding universities guarantee two years’ work. In this campaign, casualised staff argue that they are a way for universities to distance themselves from taking responsibility for the academic labour that enables them to function. They argue that this is devastating at the time when those staff cannot seek out new contracts elsewhere because they are in lockdown. They argue that this has ‘devastating consequences’, including amplifying the already ‘unsustainable requirements for survival in this sector’.

FOUR. Never waste a crisis

in this, we might argue for solidarity across academic labour, between casualised, tenured and senior academics. However, an analysis of the class composition academic labour demonstrates how privilege and status, alongside normalised performance imperatives, infect the possibility for solidarity. During the #fourfights action I was especially critical of professors, who are responsible for maintaining the motive, anxious and competitive energy of the academic peloton.

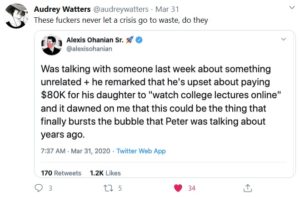

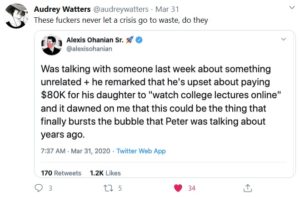

In the context of a lack of solidarity, Capital has the ability to weaken academic labour further. The inestimable Audrey Watters has noted how those who wish to disrupt or transform higher education, including venture capitalists, silicon valley entrepreneurs, policymakers, and institutional senior managers will always seek to make capital from a crisis.

Here, the focus upon the lesser-value of watching college lectures online maps across to the lack of discussion around the use of educational technology and its implications for labour relations and working practices. Capital uses technology to strip labour of its intellectual content, and to commodify the general intellect of society, or to claim it as its own inside new forces of production. This tends to reduce the value of labour. Yet there has been next to no discussion of guiding principles around the accelerated move to online teaching, assessment and student support, in terms of no detriment to staff (as opposed to students in relation to assessment) and best endeavours by staff in working under conditions of extreme stress. Equally, there has been next to no discussion framed by care and compassion towards staff as they seek to transform their own practice and pedagogy in short-order.

Thus, staff are at risk of further proletarianisation of their working conditions, and a rise in the organic composition of their work (the relationship of their labour-power to new and intensified forms of technology, flows of data, algorithmic management, digital and physical infrastructure). Already, we hear stories of excessive workloads, overwork and a lack of self-care, as academics ensure that they can meet institutional demands for business continuity or business-as-usual. Some of this anxiety is grounded in uncertainty over the future, and the need to conform to potentially punitive, institutional policy frameworks, which place risks at the feet of the individual rather than the institution.

This amplifies already existing concerns over workload intensification for HE labourers. Moreover, it amplifies already existing concerns over workplace monitoring and management that have been flagged in terms of facial recognition and the end of privacy, sentiment analysis on campus, and the use of phone tracking on campus. Now we have institutional responses that couple in engagement with ‘new pandemic edtech power networks’, which state that technologies are palliative rather than for critical care, alongside the acceleration of cost-cutting across institutions in relation to precarious staff.

For Marx, analyses of crisis are complex and highlight interrelationships between consumption, production and profitability. Issues to do with profitability, labour’s share of social wealth, the anarchy of competition, and disconnections between the forces and relations of production mean that ‘[t]heories of pure disproportion are as wrong as those of pure under consumption’ (Grundrisse, 1993, p. 751). Contradictions immanent to capitalist growth emerge from the demand for ‘a rising rate of profit and an expanding market’, which cannot be sustained because ‘revolutions in technology and organisational development’ both increase average labour productivity and subsequently reduce the amount of labour embedded in each commodity (ibid.). As a result, periodic crises of value are reflected in ‘[a]ccelerated capital accumulation’, ‘an increase in organic composition’ of capital, ‘a decline in the rate of profit’, and weak investment (ibid.). It is no wonder that families might question the value of a degree predicated upon watching lectures online. It is no wonder that institutions feel this work can be done at a lower cost.

In this, performance measurement and management bring the relationships that emerge in the classroom into stark relation to the market. The key moment in this process is the need to generate surplus value, through exchange and enterprise. HE policy points towards the importance of improving the quality of marketable data, in order to enable employers, institutions and credit agencies to make more informed judgements about individuals through risk-based analyses of past, present and potential performance. What happens inside the classroom, or the bedroom, the kitchen table, the space under the stairs, or wherever you are forced to work from home, becomes a primary, societal concern that is dominated by exchange rather than social use, and governed by quality regimes rooted in the management of risk.

Need to care for your children? You also need to demonstrate the value of your human capital. It is probably best if you do not have caring responsibilities, or if you cannot offload those somewhere else. And definitely try not to get ill. In this way, the medical pandemic catalyses the crisis of capital, which acts as a predatory mechanism for renewing regimes of value accumulation. Unproductive capitals, including unproductive human capital, can be eviscerated or decomposed, and their component commodities, or the surplus that their decomposition releases, can be recombined or accumulated in new forms, technologies or modes of organisational development. Equally, they can simply be deployed by cheaper capitals, including those whose human capital is cheaper.

Never waste a crisis.

FIVE. The pandemic, overwork and being rendered surplus

It was ever thus.

In his mid-40s, John had worked as a casual university tutor since finishing his PhD in philosophy 15 years ago. Passed over a few times for tenured jobs, he was a long-term member of the academic reserve army, the members of which perform around half of the undergraduate teaching in Australia’s universities.

But this semester no offer of work came through from any of the universities he had worked for over the years. Without income to pay the rent, and deprived of institutional anchorage for his vocation, we can see now that his predicament was dire.

As a casual you inhabit the zombie zone beyond the ivory towers – never fully asleep, nor awake – a temporary colleague at best.

Morgan, G. (2016). Dangers lurk in the march towards a post-modern career. The Sydney Morning Herald.

I am of the opinion that you are struggling to fulfil the metrics of a Professorial post at Imperial College which include maintaining established funding in a programme of research with an attributable share of research spend of £200k p.a and must now start to give serious consideration as to whether you are performing at the expected level of a Professor at Imperial College.

Over the course of the next 12 months I expect you to apply and be awarded a programme grant as lead PI. This is the objective that you will need to achieve in order for your performance to be considered at an acceptable standard

Please be aware that this constitutes the start of informal action in relation to your performance, however should you fail to meet the objective outlined, I will need to consider your performance in accordance with the formal College procedure for managing issues of poor performance.

Email sent by Martin Wilkins to Stefan Grimm, 10 March 2014.

One of my colleagues here at the College whom I told my story looked at me, there was a silence, and then said: “Yes, they treat us like sh*t”.

Email from Stefan Grimm to various associates, 21 October 2014.

We ought to be acting on it. We ought not to be leaving staff thinking they are alone in being unable to manage their workload and that there’s some particular weakness on their behalf that they can’t do it. Because in the end that is what you are left feeling.

Professor Victoria Wass, commenting in 2019 after the inquest into the suicide of Dr Malcolm Anderson at Cardiff University Business School.

It was ever thus.

A while back I wrote about academic overwork, in relation to the desperate, competitive fight for surplus value (monetised, financialised, marketised) across the HE sector of the global economy. I wrote about how overwork is revealed through academic quitlit, in narratives about bullying, in discussions of mental health and academia, and, shockingly, through reports of suicides. These narratives and histories enable academics and students to be classified as precarious or without status, or lacking human (cognitive) capital, or even lacking emotional resilience. In this focus on academic overwork there is an intersection between academic ego-identity, control of the human capital that is the life-blood of the reproduction of the University as a competing business, and the internalisation of performance management/anxiety.

I note that what emerges, through the social relations of higher education “is an academic arms-race that we cannot win.” This drives competition between academics, between academics and professional services staff, between academics and students, between subject teams across universities, between higher education institutions, and so on. Competition for students, over scholarly publications, and most importantly, over time, means that we have no control over the surplus time that the University demands from us, and that the university seeks to manage though workload planning, absence management, performance management, teaching/research excellence.

Don’t be a carer. Don’t be ill. Don’t render yourself surplus. Do overwork.

Universities require an abundant supply of flexible and appropriately-skilled labour-power as a means of production, in order to address fluctuating demand in the delivery of teaching, scholarship, research and knowledge transfer. The key to increasing the rate of valorisation of capital is the ability to generate surplus value, in its absolute or relative forms, and employing labour-power as cheaply as possible is crucial. This then requires a level of overpopulation or a reserve army of labour that can be used to drive down costs (including wages, staff development costs, pensions and so on).

There are a series of processes that can drive costs down further, and maintain competitive edge in a global market. Universities might become more capital-intensive, by investing in technology and organisational development (restructuring, new workload models and so on). This increases the organic composition of capital, by increasing the ratio of constant capital to variable capital that is deployed. Clearly, this leads to problems in the production and accumulation of surplus value, which can only be generated through the exploitation of people as workers. As more constant capital or means of production (e.g. in terms of technology) are set in motion by an individual labourer, there is a pressure to economise on labour-power (as a commodity) or to discover new markets.

If the higher education sector were to maintain employment as a constant, universities would need to expand (to generate a larger capital to support employment) or a higher rate of accumulation (of surpluses) would be required. Yet as more rapid accumulation has concomitant increase in the organic composition of capital, this produces a “relatively redundant working population” which is underemployed or becomes unemployed. As a result, there is an increasing set of pressures on labourers to remain employable in businesses and sectors that are increasing their organic composition, and this is manifest in the need to demonstrate perpetual entrepreneurialism.

In Capital, Marx articulates the formation of the reserve army of labour as a necessary component of the relationship between the forces and relations of production.

in all spheres, the increase of the variable part of capital, and therefore of the number of labourers employed by it, is always connected with violent fluctuations and transitory production of surplus population, whether this takes the more striking form of the repulsion of labourers already employed, or the less evident but not less real form of the more difficult absorption of the additional labouring population through the usual channels.

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1.

As Marx notes, economising and developing the forces of production interrelates with the relations of production, which for many academics and students becomes increasingly precarious, bureaucratised and digitally-enabled. As a result, in spite of the best endeavours of academic staff under the pandemic, there is a flow between:

- the need for universities to compete and to remain productive through technological and organisational innovation;

- the ability of universities to drive down the labour-time for assessing/teaching/publishing compared to competitor institutions, so that it can maintain competitive advantage;

- the concomitant rise in casualised or precarious employment, because by driving down labour costs university senior managers buy a greater mass of labour power or ‘progressively replaces skilled labourers by less skilled, [and] mature labour power by immature’;

- changes in the technical conditions of the process of academic production (through digital innovation, new workload agreements, and so on), which enable new accumulations of surplus academic products to become additional means of production. This drives new markets, or internationalisation or digital learning strategies, and offers the possibility of throwing academic labourers from one sphere of production (the university) into new ones (private HE providers or alternative service providers);

- the ability to sustain surpluses, as concentrations of accumulated wealth, in part by forcing academic labour to set in motion more means of production, in order to reduce the relative size of its labour costs, and even worse to become self-exploiting entrepreneurs;

- the ‘accelerated accumulation of total capital’ required to absorb new (early career) academic labourers or even those already employed, through the constant revolutionising of the means of production and the search for new markets for expanded cycles of accumulation; and

- the drive to centralise and monopolise the production, circulation and accumulation of academic value (through league tables, enabling market exit, and so on), which changes the composition of capital by increasing the constant, technical parts (the estate) and reducing the variable costs of labour).

It is in Marx’s analysis of the composition of the relative surplus population that we see the impact on academic labour through three forms of the relative surplus population. First, the floating or those who are precariously employed, and whose employment is affected by cyclical fluctuations in recruitment or funding, or by the deployment of innovations, or the employment of cheaper (younger) workers. Second, the latent form refers to those whose work is easily transferred across sectors, such as those with menial or leverage skills. Third, the stagnant form consists of very irregular employment on very bad terms. Crucially for Marx is the idea that these three elements of the reserve army of labour, alongside paupers and the lumpenproletariat, in their relationship to the working class, then offer a theory of the internal differentiation of the working class.

One might see this in the status distinctions between tenured, non-tenured, contract and sessional teaching staff, or between institutional bureaucracies, academics and professional service staff, or between full-professors, associate professors, lecturing staff, research fellows and research assistants, and so on. However, one might also use these categories to analyse academic and student overwork in response to: first, the threat of more efficient labour that can attract research or teaching excellence funding; second, the threat of cheaper labour, be it international or domestic and precarious; and third, senior managers’ demands that they become perpetually efficient and entrepreneurial. Here the content of academic labour, the teaching, preparation, assessing, feedback, knowledge transfer, curriculum design, scholarship, and so on, is reinvented entrepreneurially. New forms of the academic division of labour are internalised, and where the academic is unable structurally or personally to deliver superhuman capabilities, their labour risks becoming simplified, worthless or made superfluous. Or their inability to mourn their lost academic egos becomes rooted in melancholia.

The attempt to become superhuman, in generating and offering-up surplus labour time, generates overwork just as it responds to and reinforces the surplus, reserve army of academics. In this process overwork or surplus labour, and the generation of a reserve army, enable universities to generate new models for performance and competition, and for engaging in financialised growth and market-based exploitation.

[T]hey mutilate the labourer into a fragment of a [human], degrade [them] to the level of an appendage of a machine, destroy every remnant of charm in [their] work and turn it into a hated toil; they estrange from [them] the intellectual potentialities of the labour process in the same proportion as science is incorporated in it as an independent power; they distort the conditions under which [they] works, subject [them] during the labour process to a despotism the more hateful for its meanness; they transform [] life-time into working-time, and drag [dependents] beneath the wheels of the Juggernaut of capital. But all methods for the production of surplus-value are at the same time methods of accumulation; and every extension of accumulation becomes again a means for the development of those methods. It follows therefore that in proportion as capital accumulates, the lot of the labourer, be [their] payment high or low, must grow worse.

Marx, K. (1867). Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, Volume 1.

As Simon Clarke has noted, in order to compete and to stave off any crisis of accumulation, institutions tend towards technological or organisational innovations by:

- increasing the intensity of exploitation;

- reducing wages below the value of labour-power;

- cheapening the elements of constant capital (raw materials including those that are intellectual in nature and machines);

- stimulating relative over-population, such as the generation of a body of cheap workers (like graduate teaching assistants and post-graduates who teach); and

- stimulating internationalisation strategies, in order to enable exports and new markets for accumulation, as well as cheapening the elements of constant and variable capital.

What emerges in any discussion of the political economy of academic labour is that competition, as a function of the need to become productive of value and to accumulate surplus value or surpluses, worsens the position of the worker be she academic or student.

SIX. The pandemic and academic asphyxiation

Our labour acts as an expanding circuit of alienation. It is a withering form of living death rooted in personal losses that expels caring responsibilities or the concerns of the precarious from its own orbit, forcing those who labour inside the University to internalise the costs of caring or precarity. The truth is that academia is not privileged and that it is not a labour of love and that in the process of fetishising it we diminish ourselves. This idea that academics fetishise and universalise their own labour as an objective, public good does nothing but cripple any hopes of self/social-care or renewal.

Academics have been nudged towards accepting these forms of crippling enslavement by focusing upon the alleged privilege of working in education, and the self-sacrifice of public service. This has been a way in which capital has been able to compel overwork and exhaustion across a social terrain… Estrangement from the self emerges from the loss of subjectivity and sensuous, creative practice, inside relations of production with increased technical composition.

Hall, R. (2018). The Alienated Academic: The Struggle for Autonomy Inside the University. London: Palgrave Macmillan, p. 169.

As a growing surplus population drags the experience of exploitation and immiseration from the margins of academic society into its core, through performance management and precarious employment, there is potential for indignation and degradation to be generalised. At issue is how to place transformation of the mode of production at the heart of the matter, rather than amplifying hopelessness. As practices from the racialised, gendered, disabled, homosexual and queer margins of the global North and the global South move back to the centre of production, engagement in survival programmes as a precursor to dismantling the mode of production, are crucial for academics. Academic privilege and hegemonic, alienating academic norms need to be checked by learning from alternative life experiences. This demands a new war of position in the name of survival pending revolution, rooted in co-operation and accepting of the reality that Keynesian, welfare capitalism cannot be reinstalled. Instead, academic hopelessness needs to stimulate an alternative social function as the basis for abolishing wage labour.

Hall, ibid., p. 181

Through the pandemic, it is not enough to discuss academics as a homogenous group or with an ability to work collectively to confront their conditions of production, in order to challenge the relations of production that are so clearly toxic to so many. It is clear that academics exist in a range of constantly shifting, determinate conditions, which are re-shaping the ways in which academic labour functions through the application of new forms of organisation, precarious employment, rounds of voluntary severance and reorganisation, the imposition of new technologies, policy edicts which drive competitive demands, and so on.

Moreover, these conditions are different for a range of sub-groups and communities of whatever academia is or might be. Where the experience is defined by norms set against the idea of the successful White, male, heterosexual, able Professor, the rest of the academic peloton is forced to recalibrate itself will be recalibrated by this privilege. What this then means if you are an academic of colour, female, have a caring responsibility, are ill, whatever, is that you have to suck it up or take that next course on mindfulness or resilience, or decide that perhaps this isn’t the place for you.

The duality of the medical and financial pandemic signals the depth of the structural crisis of capitalism, and it has implications for the class composition of University workers as more and more people are dragged towards proletarian working conditions. This reminds us of the argument of István Mészáros in The Structural Crisis of Capital (2010, p. 172) that such crises reveal ‘the activation of the absolute limits of capital as a mode social metabolic reproduction’. Capital is unable to reproduce itself without asphyxiating those upon whose labour its subjectivity relies. Without access to ready markets for recruitment, commercialisation and impact -related possibilities, or escape routes grounded in public engagement and knowledge transfer, the University becomes unable to reproduce itself without asphyxiating those upon whose labour its subjectivity relies.

SEVEN. For humanity?

The Institute for Precarious Consciousness calls for the addition of “a machine for fighting anxiety”. They argue that we need to:

- Produce new grounded theory relating to experience, to make our own perceptions of our situation explicit, recounted, pooled and public;

- Recognise the reality, and the systemic nature, of our experiences;

- Transform emotions through a sense of injustice as a type of anger which is less resentful and more focused, and as a move towards self-expression and resistance;

- Create or express voice, so that existing assumptions can be denaturalised and challenged, and thereby move the reference of truth and reality from the system to the speaker, to reclaim voice;

- Construct a disalienated space as a space for reconstructing a radical perspective; and

- Analyse and theorise structural sources based on similarities in experience, to transform and restructure those sources through their theorisation, leading to a new perspective, a vocabulary of motives.

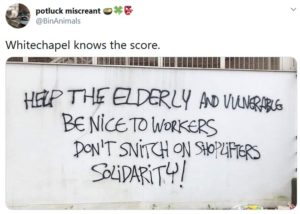

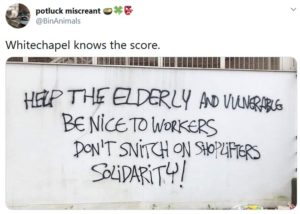

The editorial collective of Society and Space indicate the importance of pressing pause at this time. They indicate the importance of slowing the system, is a more ethical and tenable response. This enables us to think about the interrelationship between our broken healthcare and education systems, and how care and compassion are marginalised by the demand that we return to the market to sell our alienated labour-power. Instead, tentatively and modestly, they point towards the different ethos in the future post-pandemic(s). Ioana Cerasella Chris amplifies this in thinking about uncertainty at the level of society and our sociability. Here, the current conjuncture sees labour rights, economic populism, austerity politics, eco-fascism, and on and on, erupting from structural crises. As a result, the exploited core needs to reflect upon the expropriated margins of the global economy, in order to refocus solidarity with:

low-paid workers across the globe are the ones who are keeping everyone safe, and whose jobs are ‘key’ and socially necessary; we can also see how trade unions and disabled people’s organisations are at the very heart of the struggle for better safety measures and protections for all.

For Marx in The German Ideology this has to be addressed communally, by pushing back against the division of labour and recovering the humanity of their material powers. This is only possible through association, and in cooperation, and with guiding principles that are mutual, and through the community. Where community is mediated by the State or institution, personal freedom and autonomy is a function of one’s relationship to privilege, status and power.

It is the proletariat who, for Marx, act as the revolutionary class. Inside the University, it seems that the potential for change stems from those workers with nothing left to lose. This means that such a workerist analysis of the condition of academic work needs to consider how that work is integrated into capitalist social relations and relations of production. It needs to consider the divisions that exist between academics, and how those divisions or separations are maintained. Moreover, such a(n academic) workers’ enquiry might connect academic labour to the idea of autonomous activity outside the University and whether they offer moments of subversion or transgression against the value-relation. This demands that academics see their conditions of labour as continually-changing, and that the only redemption lies in accepting the hopelessness of a compact with a system of exploitation.

Without such a theorisation it becomes impossible to negate the capital-relation through the expansion of the realm freedom and autonomy. Instead, the focus becomes about issues of free speech, academic autonomy, resistance to casualisation, and other tactical reforms of an otherwise brutalising system. [Revolutionary praxis] entails a focus upon the production of the self as a pedagogic moment grounded in self-mediation as the key organising principle for life.

Hall, ibid., p. 248