I

In an excellent article on Technology, Distribution and the Rate of Profit in the US Economy: Understanding the Current Crisis, Basu and Vasudevan scope the connections between falling capital productivity, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall, and technological innovation. Specifically they argue that the period preceding the current financial crisis in 2008 witnessed a significant and sharp fall in capital productivity and hence in profitability, and that this counteracted the rises that were accrued from the widespread implementation of information technology, techniques of new managerialism and the tendency towards financialisation in the previous three decades.

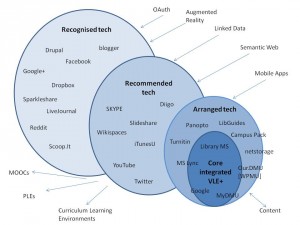

In understanding the changes that are impacting the higher education sector, developing a critique of the relationships between technology and technological innovation, new managerialsm and financialisation, and the impact of structural weaknesses in global capitalism, is critical. Moreover, it is important to critique these changes historically and geographically, in order to understand how political economics shapes the space in which higher education policy and practice is recalibrated for capital accumulation and profitability. I am trying to develop the argument that we need to examine educational innovations like open educational resources, MOOCs, bring your own device, personal learning networks etc. in light of the relationships between: technological innovation; the competitive demand to overcome the historical tendency of the rate of profit to fall; the disciplinary role of the integral State in shaping a space for further capital accumulation, against labour; and the subsumption of networks and network theory to the neoliberal project of accumulation and profitability.

This is an on-going discussion and this post is a starting point for some ideas that will develop over time, in particular in trying to understand how technologically-mediated innovations might be analysed alongside critical pedagogy, in order to demonstrate alternative positions.

II

Historically technological innovation has been seen as a response to economic stagnation or to crisis, not simply to act as a brake on wages but also to renew capital productivity. However, for the period immediately prior to the financial crisis of 2008 this does not appear to have been the case. Basu and Vasudevan argue:

The investment-seeking surplus generated by the enormous and growing productivity of the system is increasingly unable to find sufficient new profitable investment outlets [my emphasis]. Monopoly capitalism faces a tendency toward stagnation as a consequence of the gap between the growing economic surplus and existing outlets for profitable investment. There is a continual need to find new ways to profitably invest its surplus and new sources of demand. But rather than invest in socially useful projects that would benefit the vast majority, capital has constructed a financialized “casino”. Capitalism in its monopoly-finance capital phase becomes increasingly reliant on the ballooning of the credit-debt system in order to escape the worst aspects of stagnation.

This then underpins a structural weakness at the heart of the global system of capitalism, which has seen a tendency to overproduction and a decline in the return on capital investment in manufacturing and productive sectors of the economy. This in-turn has underpinned both an attrition of real wages since the 1970s and the flight into precarious and immaterial labour and the valorisation of virtual or cognitive labour, alongside the ideas that promote creativity and enterprise as levers of economic renewal. Historically this has also witnessed debt-driven investment in education, through: a turn to vehicles like increasing student fees and the bond markets; opening-up the sector to marketised solutions, outsourcing and hosted services, shared services, and human capital controls (in student numbers, in legitimating certain groups of foreign students, in restructuring labour etc.); and, a focus on shackling the subjectivity of labour to governmentality through performance measurement and surveillance. Thus, higher education continues to witness the implementation of technologies for value extraction, command and coercion.

In this process, technologies for sharing, for service-driven innovations, for ubiquitous computing, for personalisation etc. are seen to be strategically critical. This reflects Marx’s emergent mature work, in which technological innovation is linked to capital accumulation and increasing profitability. Developing a technological lead drives competition between businesses or between different capitals, and this drives the production/consumption cycle and hence profitability. Competition compels other capitalists towards technological innovation and increasing capital intensity, in order both to extract a larger surplus from their own labour-force, and to discipline that labour-force under the threat of restructuring or unemployment. This is an on-going pattern of technological change driven by a need to extract surplus value and decrease dependency on variable labour costs.

For Basu and Vasudevan, the period leading up to 2008 was critical in recalibrating the economies of the global north around the widespread adoption of technologies and new managerialism. They argue that

The pervasive adoption and growth of information technology would have almost certainly played an important role in shaping the particular evolution in the nineties when capital productivity showed an upward trend. New forms of managerial control and organization, including just-in-time and lean production systems have been deployed to enforce increases in labor productivity since the 1980s. The phenomena of “speed-up‟ and stretching of work has enabled the extraction of larger productivity gains per worker hour as evidenced the faster growth of labor productivity after 1982. People have been working harder and faster. Information technology has facilitated the process. It enables greater surveillance and control of the worker, and also rationalization of production to “computerize” and automate certain tasks.

Critically the fall in cost of hardware and software infrastructure meant that productivity gains were achieved with smaller increases in capital outlay. In terms of UK HE, a large part of the initial development costs for innovation and development in educational technologies was state-subsidised through project-funding, transformation programmes, and investments in national infrastructure. This lowered the cost of capital investment for individual universities or colleges as competing capitals. One result is that labour-productivity has been increased without necessitating increasing capital intensity, and thinking about the sector as a whole, rather than individual universities as businesses, this has also been catalysed by globalisation and outsourcing services that are of low value and jobs that are of low surplus value extraction.

The twin problems for capital of this approach are of declining rates of accumulation, as the increase in the organic composition of capital tends to diminish the rate of profit where there are fewer employees to exploit and more technology or techniques to manage, and a fall in local capital intensity or productivity through what Marx called moral depreciation. In Capital, Volume 3, Marx argues that over time “moral depreciation” affects the gains made by technological innovation where the new machine

loses exchange-value, either by machines of the same sort being produced cheaper than it, or by better machines entering into competition with it. In both cases, be the machine ever so young and full of life, its value is no longer determined by the labour actually materialised in it, but by the labour-time requisite to reproduce either it or the better machine. It has, therefore, lost value more or less. The shorter the period taken to reproduce its total value, the less is the danger of moral depreciation; and the longer the working-day, the shorter is that period. When machinery is first introduced into an industry, new methods of reproducing it more cheaply follow blow upon blow, and so do improvements, that not only affect individual parts and details of the machine, but its entire build. It is, therefore, in the early days of the life of machinery that this special incentive to the prolongation of the working-day makes itself felt most acutely.

As a result, the drive under the treadmill logic of competition becomes to deliver constant innovation across a whole socio-technical system, in order to maintain or increase the rate of extraction of relative surplus value, and to tear down the barriers of under-consumption. This implication is crucial inside a higher education sector that is being recalibrated for enterprise inside a competitive system, and where technological innovation is perceived to drive profitability.

Historically, we have witnessed a technological recalibration of the higher education sector under the drive for productivity and efficiency, and in the name of an enhanced student experience that is managed through techniques like the national student survey. The subsumption of universities-as-businesses, or as competing capitals, further amplifies this process. However, it also disciplines the investment decisions of those individual businesses, which are no longer underwritten by the State as a backer of last resort, and this threatens a new vulnerability that is manifested in capacity utilisation, a squeeze on production/product prices, and the need to maintain profitability. The growth of financialisation in the sector, in order to protect investments, might temporarily alleviate any weakness of demand for the products of the university. However, in the medium-term, individual universities are constrained by the structural weaknesses of the global economy that are loaded towards financialisation and the ongoing process of deleveraging private debt as public liabilities, the need to become profitable in a market, and new forms of competition from private providers. These new forms of competition might be rival organisations with degree-awarding powers, or they might be partnerships of accrediting organisations operating through MOOCs, or they might be hedge funds providing venture capital for technologically-driven innovations.

III

In their paper Why does profitability matter? Duménil and Lévy argue that profitability and stability are linked, and that the rate of expansion of a capitalist economy is underpinned by the general rate of profit that can be generated, the capital that can be accumulated is then re-invested for further surplus value extraction and profitability. This underpins investment decisions and technological innovation. Thus, as Basu and Vasudevan note:

It is equally important to untangle the drivers of profitability, to decompose the rate of profit into its underlying determinants. The trends in labor productivity, capital productivity, and profit share are important in unraveling the role of technology and distribution in determining the trajectory of the profit rate.

In untangling these drivers in the global economy, the role of networks and networked learning has been emphasised as a driver for economic renewal and growth. Jonathan Davies has written extensively, critiquing network governance, and has pointed out that the idea of the ‘network society’ is complex and contested, and that it rests on some simple claims.

- That modern capitalist society is too complex, fragmented and disordered for effective command management.

- That universal education enables us to challenge power, undermining our traditional commitments to family, faith, flag and fraternity.

- That the universal welfare state and rising prosperity liberate us from narrow and selfish economic concerns, creating the conditions for a more sociable and trusting personality to emerge.

- That ubiquitous communications technology provides the infrastructure for clever, critically-minded, prosperous and sociable people from all walks of life to connect with one another in pursuit of their ever-changing projects and goals.

As Davies notes, these precepts form the building-blocks of ‘horizontalism’; the belief that we live in a world of networks, that networking is a good thing to do, and that we can only understand the world if we apply network-theoretical concepts.

In this view, not only does the network apply to government-citizen partnerships, knowledge transfer, community engagement and so on, but also to projects of opposition to governmental agendas like those related to austerity. Thus, opposition is often framed by the idea of the multitude as distributed, decentred, swarming sets of resistances that form flows or circuits against a capitalist project that is represented as an Empire of accumulation. Thus, whilst the network forms a space for accumulation and profitability, it is also a counter-hegemonic space designed for organising resistance, for developing solidarity through occupation, for developing militant responses to the creation of the edufactory, for general assemblies, or for the work of groups like Anonymous.

Yet as Davies argues, ‘network governance is part of the hegemonic strategy of neoliberalism – the visionary, utopian and profoundly flawed regulative ideal of late capitalism.’ Network governance in this view is a problem-solving strategy, designed to make the capitalist project function more smoothly, rather than emerging as a strategy designed to critique the power-relations that exist inside capitalism, in order to overthrow them. Thus, the network is directed towards functionalism, for unearthing practical solutions to practical problems, based on a normative bias towards trust-based relationships nurtured inside networks that are often technologically-mediated. Thus, connectionist [or cybernetic] capitalism is described in terms of autonomy, rhizomes, spontaneity, multi-tasking, conviviality, openness, availability, creativity, difference, informality, interpersonal connections and so on. This underpins the idea that postmodern capitalism is weightless or infinitively creative, diverse and immaterial.

Crucially, Davies asks questions related to the relationships between governance networks and network governance. The latter is an ideal-type that rests upon the post-structural claim that the network is proliferating in form and underpins our everyday activities, based on ethical virtues like trust and empowered reflexivity. Network governance is seen to be a rupture with the past. The idea of the governance network refers to recurring and/or institutionalised formal/informal resource exchanges between governmental/non-governmental actors. This is the space that claims a democratic, decentralised opportunity to deliver change and choice, masked as new public management. Thus, for Davies the central question becomes why governance networks do not live up to the promise of network governance, which is important in delivering for and in communities? Why do hierarchies and management for command proliferate and dominate?

In this argument the network is placed asymmetrically against the realities of hegemonic power that is catalysed and reproduced in the political and economic centralisation that is so characteristic of crisis-prone capitalist modernity. The reactions of central governments and finance capital to the post-2008 crisis bear witness to this process. For Davies then, the research evidence in the public policy, sociology and public administration spheres point to the fact that

coercion is the immanent condition of consent inherent in capitalist modernity. As long as hegemony is partial and precarious, hierarchy can never retreat to the shadows. This dialectic plays out in the day-to-day politics of governance networks through the clash between connectionist ideology and roll-forward hierarchy or ‘governmentalisation’.

Technologies are central in this clash, for whilst it is possible for some people to connect globally and ubiquitously, those same technologies form the medium of hierarchical power. The challenge then becomes to analyse how those technologies interact with the everyday reality of interpersonal connections, and to uncover the power relations that they embody. Critically this is a historical project, because network governance theory misreads past and present, ignores that networks are prone to resolving into hierarchies and incremental closure, that they reproduce and crystallise inequalities, and that distrust is common. In this way, the emergence of technologically-mediated network governance enables capital to develop and enculturate ideal neoliberal subjects.

Critical in this argument is coercion and coercive practices. For Gramsci, this rested upon the idea of the integral State, which is the product of the formal institutions of civil society and of political society. This formation underpins the creation and reproduction of instruments and artefacts of hegemony, like technologies and educational organisations, which themselves enable social resources to be harnessed in the name of accumulation and profitability. However, in order to maintain a hegemonic order that is always contested and resisted, instruments of coercion and consent are required. These instruments include techniques of surveillance and workplace monitoring or analytics, alongside pedagogies of debt and indenture, and state-backed violence against dissent. This latter point is critical because, as Davies notes, contracts have to be enforceable. Violence is integral to the commodity form and the realisation of exchange value. As a result, coercion is immanent and in dialectical relationship with consent in a continuum from direct repression to the governmental management of subjectivity.

This is the world that frames the network in education. This is the world that frames the use of technology inside education. Education is developed inside a world of hierarchy and the dialectical interplay of consent and coercion, where, as Perry Anderson noted, without state-enforced coercion and the threat of violence, ‘the system of cultural control would be instantly fragile, since the limits of possible action against it would disappear’. The network is conditional on the threat of disciplinary violence and the immanence of governmentality that, in turn, disciplines subjectivity. More brutally, for those who believe in the emancipatory potential of educational technology, and the power of connectivist networks, Friedman offers the timely rejoinder that:

The hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist. Markets function and flourish only when property rights are secured and can be enforced, which, in turn, requires a political framework protected and backed by military power… the hidden fist that keeps the world safe for Silicon Valley’s technologies to flourish is called the US Army, Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps.

IV

I want then just to write a few words about the current fetish for MOOCs, in order to open-up an avenue of thinking about hegemony and hierarchy in higher education, and the possibilities for academic labour to utilise technology to critique responses to the current crisis of capitalism that is recalibrating the sector. In this project, it becomes important to highlight, as Stephen Ball and Jonathan Davies have, the importance of network analyses that focus upon the production, reproduction and contestation of power, and the processes through which alliances, like Ball’s neoliberal transnational activist networks, that emerge from shared ideologies and resource interdependencies further reinforce asymmetric power relations. For Davies, critique needs to unearth the relationships between consent and coercion, between power and command structures, between network-like institutions and more formalised, traditional institutions, in order that the claims that are made for networks as delivering new forms of sociability that transcend structures of power and domination can be better understood. There is hope that in this process of critique the power of academic labour to produce alternative value forms, and forms of social organisation and governance for higher education, might be offered up.

Networks are important in connecting people, ideas and materials that are revealed in the relationships between technology and formal/informal institutions, and which underpin the reproduction of capitalist social relations and the need to maintain the increase in the rate of profit. However, beyond organising resources, there is a disconnection between the hoped-for humane, trust-based ideals of networked learning and the hard realities of hierarchical power. This resolves itself inside procedural problem-solving that locates, for example, MOOCs within the everyday realities of capitalism, and which in turn hope to experience them as less coercive or institutionalised than traditional educational institutions, and capable of resolving the student/teacher as a subject. The theorising of MOOCs has to-date rested on this kind of problem-solving theory, essentially based on student/teacher autonomy and participation, rather than as a transformational critique of the structural inequalities realised inside capitalism, through which the realities of wage labour make such autonomy practically impossible.

Thus, much of the discourse around MOOCs focuses upon ideas of openness and monetary freedom, and the creeping institutionalisation of alternative forms of education. David Kernohan has written about networked learning communities in which ‘Some courses are open as in door. You can walk in, you can listen for free. Others are open as in heart. You become part of a community, you are accepted and nurtured.’ Chatti focuses upon the management of networked learning in order to leverage ‘knowledge worker performance and to cope with the constant change and critical challenges of the new knowledge era’ Graham Attwell has highlighted the increasing institutionalization and rental/profit-based creep in the MOOC debate. Cathy Gunn aligns her argument with this institutional co-option of MOOCs or open courses, and she believes that ‘change in current traditions of higher education for many institutions will most likely require disruptive innovations outside of the academy first and we can see the evidence of the first seeds of that through the open course movement.

The mechanisms by which capital adapts and colonises work that takes place at the margins and then subsumes it inside the processes of self-valorisation are not new. However, for MOOCs this reality is amplified by the reflections of the team of teachers and researchers associated with the MSc in E-learning programme at the University of Edinburgh who began the development of a Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) for the Coursera platform. They argued that:

while MOOCs and the open education movement generally may not achieve everything – the democratisation of education, or the freeing of the world’s knowledge – they can achieve something. They can open up good teaching and interesting curricula to new groups of learners; they can help draw students into higher education who might otherwise not have ventured there; they can engage unprecedented numbers; and they can be a vehicle to continue to push at our collective notions of what constitutes the educational project.

Critically, this focus is then on new markets and technological approaches to opening-up new domains for profit or rent, with a secondary gain that appears to be just beyond reach, namely democratisation. An interesting side-effect of this normalisation or institutionalisation of alleged innovations like Coursera is the recent concern over the weakness of peer-assessment inside the MOOC experience by Audrey Watters.

This educational commentary then tends not to reflect on or to develop critiques of the network inside education policy and practice, or on the power of networks to reinforce hierarchy and hegemonic power-relations. This depoliticisation and lack of a political economy of MOOCs or other educational technology innovation is emerges from George Siemens’ argument that

MOOCs, regardless of underlying ideology, are essentially a platform. Numerous opportunities exist for the development of an ecosystem for specialized functionality in the same way that Facebook, iTunes, and Twitter created an ecosystem for app innovation.

This dismisses the political processes and practices that run through MOOCs, and their users’ political positions, in order to claim a neutral ‘platform’ for innovation. Siemens identifies that MOOCs

are significant in that they are a large public experiment exploring the impact of the internet on education. Even if the current generation of MOOCs spectacularly crash and fade into oblivion, the legacy of top tier university research and growing public awareness of online learning will be dramatic.

However, this significance needs to be understood inside-and-against the logic of capital’s drive for innovation in the name of the rate of profit, and its tendency to subsume labour practices inside technologically-mediated forms of coercion, command and control. This is the space against which Siemens’ claim that ‘The value of MOOCs may not be the MOOCs themselves, but rather the plethora of new innovations and added services that are developed when MOOCs are treated as a platform’ needs to be analysed. It is the ways in which MOOCs and the services, analytics, content, affects, relationships, immateriality etc. that are derived from them are then valorised that might offer a glimpse of how the neoliberal educational project is being defined and how it might be resisted and undone.

How those “services” are reclaimed in order to reproduce the structural and systemic inequalities of capitalism might also form a central strand in the development of a political economy of educational technology. This is crucial because it is about the on-going circulation and exchange of commodities inside the social factory as a central space for the production and consumption of cultural artefacts. This is central to the practices of MOOCs, for as the Change MOOC notes:

When a connectivist course is working really well, we see this greate cycle of content and creativity begin to feed on itself, people in the course reading, collecting, creating and sharing. It’s a wonderful experience you won’t want to stop when the course is done [sic.].

At issue then is how to connect the participative nature of pedagogic or educational ideas like MOOCs and the on-going aspiration for educational technology to become transformative, to the dialectical interplay between networks and hierarchies as they are resolved inside the hegemonic realities of capitalism. How might such an analysis enable alternative political projects to emerge that challenge orthodoxy and promise more than simply lifelong learning or work-based learning or learning for enterprise or learning for employability or education for growth? An approach might emerge from a historical and comparative analysis of radical education projects like the Social Science Centre that are geographically and politically grounded in a different set of spaces from network/task/informational-centric innovations like MOOCs.

A different approach might also be to align explicitly the tenets and precepts of critical pedagogy as a struggle for subjectivity, as an act of protest and resistance to dominant forms of educational structure (including MOOCs) that is designed as emancipatory practice, with the opportunities opened-up by technology. This demands that educators and technologists inside-and-beyond the university are less defensive about their work and their practices and develop alternative forms as overtly political projects. For as Amsler notes:

Any education that seeks to demystify popular ideologies; expose the subtle ways that power works through language, bodies, and representations; facilitate the imagination of radically different modes of life; and produce knowledge to orient political action represents, in various forms, a broad faith within critical pedagogical politics that there is something inherently transformative about criticality. And it is the possibility to practice such forms of education, which is, in the ascendance of the uncompromising force of market logics throughout public life, being contracted, cramped, enclosed, or foreclosed. Indeed, the need for the critical attitude has become urgent in the face of declining levels of popular support for nonutilitarian education, and a wider tolerance for complexity and otherness within the public sphere is on the decline. The overarching mood in education, including in universities, is therefore one of crisis; the broad response, one of defence.

It is through the critique of normative positions, including network governance, in response to the crisis of capitalism and the restructuring of education as a neoliberal subjectivity, that new subjectivities might emerge. The landscape for this is deeply historical and needs further political economic analysis. Whilst some emergent analysis has been attempted of innovations like MOOCs, in terms of hybrid pedagogies, the current crisis in the forms and management of the University in the global north would benefit from a deeper understanding of how educational technology and innovations are co-opted for the valorisation of capital. We might then be able to develop spaces that are networked, in which we can ask how academic labour might be reclaimed. This requires an engagement with critical pedagogy that moves higher education beyond simply addressing the tendency of the rate of profit to fall.